The Mixed Ability Family and the CODA

Booking an interpreter, a private or public state interpreter, can be challenging due to limited availability, high demand, and logistical barriers between meeting times and interpreter availability. Constantly, Deaf individuals face delays or outright denials when requesting interpreters, especially in urgent situations like medical appointments or legal proceedings, since most interpreting must be done in advance. No one can plan for receiving emergency care and properly understanding your ailment is a human right. Organizations lack awareness of their legal obligations under the ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act), or they might cite budget constraints as a reason for not providing interpreters. Additionally, last-minute cancellations or scheduling conflicts can leave Deaf individuals without access to effective communication, further exacerbating these struggles.

There is often a shared understanding between the Deaf adult and hearing CODA that any interpretation is better than no interpretation. The child taking the role of interpreter is often viewed as a practical solution. The right to The CODA, often acts as an unofficial interpreter in situations ranging from medical appointments to mundane social interactions.

The responsibility of CODAs and within the Deaf family highlights the broader need for society to create inclusive structures where Deaf individuals have equal access to resources and CODAs are not automatically placed in the role of interpreters by default.

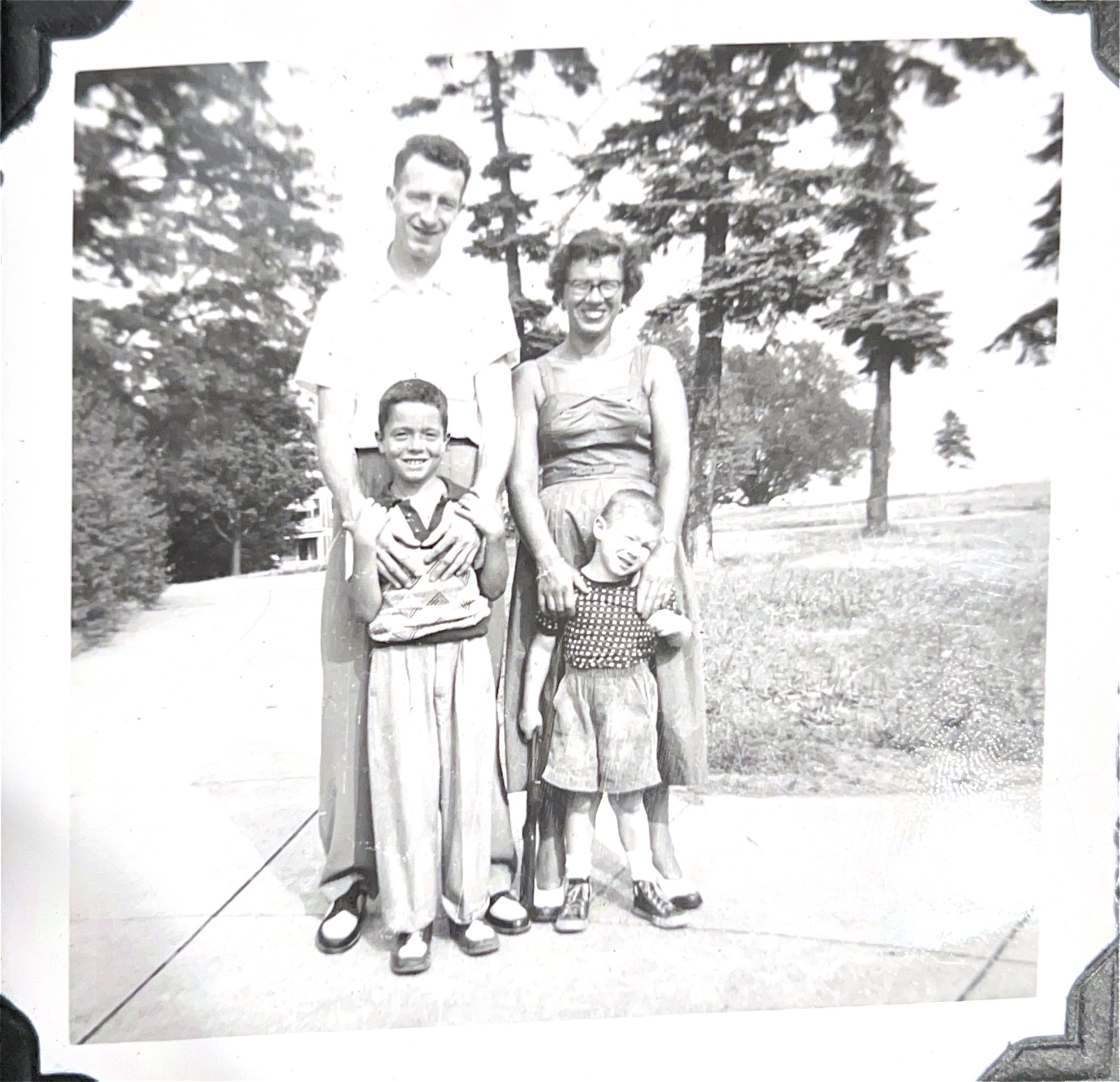

The responsibility of the CODA is often passed on with time to the youngest child in the family. In the case of the Horrigan household, the inheritance of the interpreter role was passed on to my grandfather, David, the youngest, to bridge language gaps. My grandfather was named after his grandfather and an important part of the Horrigan family.

The eldest son of the family, John Horrigan Jr., never fully became fluent in sign language. So, David often acted as an interpreter between parents and siblings within the household.

David interpreted for John and Louise for medical appointments. Even with American Sign Language as David’s first acquired language, the role of an interpreter who is well-versed in medical terminology between both translated languages is a human right for the deaf individual.

Beyond Deaf cultures, the multi-language household often relies on the bilingual child for language mediation, regardless of the nature of the conversation. The dominant society often expects the CODA to mend language barriers rather than the Deaf parents, pointing to systemic challenges, such as the lack of widespread accessibility for Deaf individuals, including interpreting services.

In a hearing-centric world, Deaf people often rely on the closest hearing kin to bridge language gaps when interpreters are not present or granted by request by the Deaf individual. Statistically, 90% of Deaf couples will have a hearing child. More often than not, the hearing Child of the Deaf Adult (CODA) feels responsibility or is often expected to take on the responsibility of being an interpreter for the Deaf parent.

Many Deaf families have multiple children, so each child of the Deaf adult(s) will experience life as a CODA with varying responsibilities.

While the CODA is given a space to foster bilingual, bimodal, and bicultural competencies, this can also lead to complex emotional dynamics, as CODAs might feel the weight of responsibility at a young age.

Growing up a CODA

Louise and John’s children, John Jr. and David, both initially struggled with literacy. While signing was the main language of the household, the only spoken words came from their Italian grandparents, leading to John developing the Italian language even before English. The school was concerned and requested that English be the main language of the household. John was too worried to inform his teachers that English as a main language would never be fully possible in a culturally Deaf home.

David and Ann Marie Horrigan on their Wedding Day, August 12th, 1967

John and Louise’s youngest son, David, met my grandmother, Ann Marie, when they were young children. They began dating as young adults in their teenage years. It became obvious to the Horrigans and my grandmother's family that David and Ann Marie wanted to start a life together.

Ann Marie’s parents were adamantly against David and Ann Marie’s relationship, largely due to the fact that David’s parents were Deaf. The possibility of Ann Marie and David having a Deaf child was too troubling to imagine for Ann Marie’s family. They did not want Deaf grandchildren or Deafness to be in the family. At this point in time, in the late 50s, unfortunately, this was viewed as a condition brought on by a hearing society that viewed deafness as a disability.

Ann Marie and David eloped in April of 1967 but re-newed their vows back home with their families in the Catholic Church. Both my grandparents talk of that day being very sad; everyone present knew that Ann Marie’s family disapproved of their marriage. Louise and John welcomed Ann Marie with open arms. The only pictures I found of Ann Marie and David both smiling that day were when Louise and John were in front or behind the camera.

Ann Marie, David, Louise, and John all continued to embrace their family and included them in their Deaf community. Grandchildren were born and learned to sign quickly. There was communication on many levels. My great-grandfather attended all of my school concerts and plays; no one even knew he was Deaf. My parents have always been able to sign fluently and loved being a part of the Deaf world.

My sister recently had a little girl named Louise, after my great-grandmother, and I have already started her journey of communication with the introduction of signs. Culturally Deaf, once seen as a disability, is my family’s unique passion for communicating, and we seek out those who appreciate our special world.

It wasn't until David was in second grade that the school started requesting that he read with his family more, as his reading comprehension was falling behind in comparison to his classmates

He recalls his teacher asking him to “sound out” the words on the page with a parent. David, in fear that he would upset his parents, kept this information from Louise, and John Sr. CODAs often feel the responsibility of protecting their image around their parents. The CODA knows a lot is expected of them and not wanting to jeopardize the trust their parents have in them, they often try to be ‘perfect’ for the Deaf parents.

David ended up being held back a year due to not telling anyone about his troubles in school. His teacher eventually found out about his CODA status and helped him the following year to catch up again.

Everything happens for a reason because David was moved into the school year of his soon to be wife.

Auntie Margaret signs to Louise Sullivan, October 2024.